Leverage: who’s leveraging who?

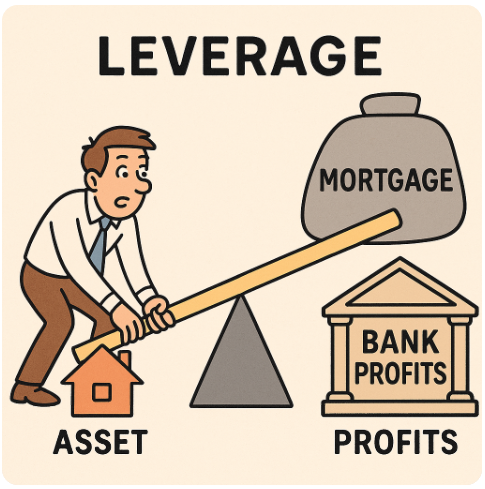

The term leverage is often used casually but frequently misunderstood. At its core, leverage refers to the use of a tool or instrument to lift or move something that would otherwise be too heavy to manage alone.

In the financial world, leverage means using borrowed money to generate additional capital through investments. The objective is for the returns on those investments to exceed the borrowing costs, thereby producing a profit for the individual who employs leverage.

It is essentially the practice of using someone else’s money to create personal wealth, but it carries significant risk. Leveraging should not be confused with liquidation, though there are certain similarities.

Using an asset as collateral to borrow funds is a form of self-liquidation. For instance, when you take out a mortgage, you are essentially trading ownership for money, with the sale only finalized if you fail to repay. As long as obligations are met, the asset is seamlessly repurchased through regular payments.

On the other hand, selling your own assets to invest in a venture is not leveraging; it is exposing yourself to great risk. Experts often consider the S&P 500 to be the most reliable long-term investment for ordinary investors, yet the accessibility of stock markets has led many to take chances with trading.

A homeowner who continually layers mortgages, even for the purpose of purchasing more property, is in fact liquidating their equity to take on more debt. Each additional mortgage represents a swap of built-up equity for further obligations.

Recent years have seen this behaviour fueled by fear of missing out, spurred by government lockdowns, quantitative easing, and mass migrations. Many speculated heavily in real estate, expecting values to continue climbing and returns from flipping or renting to be substantial.

However, as housing prices rose while incomes remained stagnant, affordability inevitably declined. Those unable to buy property began liquidating safer investments such as self-directed RSPs held in GICs and mutual funds, converting them into high-risk promissory notes.

This behaviour benefited central and chartered banks by injecting money into the system. Governments still count liquidated assets as part of the average Canadian’s investment portfolio until completely written off, creating a misleading picture of wealth.

Every private promissory note issued was backed by at least one bank or investment company mortgage. Traditional lenders reduced their risk exposure, while private speculators bore elevated risks. Put simply, bankers were leveraging your self-liquidation.